Images

- Campari Soda (bottle)

- Campari Soda (bottle)

- Fortunato Depero

- Fortunato Depero (1915)

- Davide Campari

- The Camparino

- Campari vending machine

- Statuette for Campari, 1926

- Sketch, 1931

- Sketch, 1926? (Courtesy of Casa d’Arte Futurista Depero)

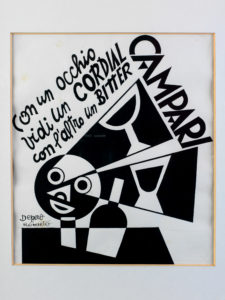

- Sketch (courtesy of Galleria Campari)

- Sketch (courtesy of Galleria Campari)

- The Bolted Book (courtesy of Galleria Campari)

- Casa Kappel in Santa Maria, Rovereto, 1923 (Courtesy of Casa d’Arte Futurista Depero)

- Casa Kappel in Santa Maria: allestimento del Salone dei Cavalieri di carta. Rovereto 1923 (Courtesy of Casa d’Arte Futurista Depero)

- Casa Kappel in Santa Maria, Rovereto 1923 (Courtesy of Casa d’Arte Futurista Depero)

- Interior of Casa d’Arte Futurista Depero (Courtesy of Casa d’Arte Futurista Depero)

- Interior of Casa d’Arte Futurista Depero (Courtesy of Casa d’Arte Futurista Depero)

- Interior of Casa d’Arte Futurista Depero (Courtesy of Casa d’Arte Futurista Depero)

- Interior of Casa d’Arte Futurista Depero (Courtesy of Casa d’Arte Futurista Depero)

- Casa d’arte Futurista Depero (exterior)

- Casa d’arte Futurista Depero (exterior)

- Casa d’Arte Futurista Depero

- Casa d’arte Futurista Depero

- Sketch of a Campari booth (courtesy of Galleria Campari)

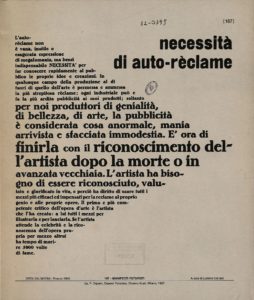

- Necessità di Auto-reclame, Manifesto, 1927

- Manifesto agli Industriali, 1927

- L’arte del Cartello, Manifesto, 1937

- Il Futurismo e l’arte pubblicitaria, Manifesto, 1931

Suggested Readings

- Daniele Baroni, Maurizio VItta, Breve Storia del Design Grafico, Longanesi

- Marina Mojana, Ada Masoero, Depero con Campari, De Luca

- Vv. Aa., Depero Futurista, Electa

- Gabriella Belli, Beatrice Avanzi, Depero Pubblicitario, Skira

- Vv. Aa., Futurist Manifestos

Suggested Sites

Music Credits

- Main Theme – Valerio Mirone

- Turning – Unheard Music Concepts

- Shame – Unheard Music Concepts

- Four-Way – William Ross Chernoff’s Nomads

- El Lentidigitador – Milton Arias

- Balkan Paranoia – Unheard Music Concepts

- Jingle Jazz – Quantum Jazz

- Passing Fields – Quantum Jazz

- Greensleeves Jazz – Doxent Zsigismond

- King Richard’s Blues – Mr Yesterday

- Orbiting a distant planet – Quantum Jazz

- Hope is like a river – Jeris

Sound Effects

- stylus – gadzooks

Transcript

What you’re hearing now is a moderate amount of Campari Soda fizzing after being poured into a tall glass. The velvety liquor fills the interstices between the ice cubes while the bottle is now empty, transparent. It has no label on it: the red liquor, shining through the conic surface of the bottle, says without a doubt that this is a Campari soda.

Despite being a familiar, even mundane object, this bottle is quite pretty and hides its beauty in plain sight. The clean, sleek design is a product of true creativity. Because there’s a difference between making something innovative, something that stands out, and making this novelty acceptable and accepted. To conceive something new and transform it into something ordinary, that is the long-lasting testament of genuine creativity. And this bottle, this little glassy thing hides an all-Italian story about one artist and the entrepreneur who made an avant-garde dream come true. Would you like to hear it? Then, bear with me, this story comes from Ars Dicendi and today we’re dealing with Italian Culture.

Welcome to the roaring twenties: the first world war has finally come to an end while modern mass society is at its dawn. The world is now a smaller place, people can hop on a train and cross a continent in a few days. Or they can turn the radio on and listen to the news from far-away lands. Ideas travel fast, even faster and cheaper than people. Modern media are starting to influence people’s opinions in a way that wasn’t possible before. Politicians are probably the first ones to take advantage of this situation, especially in Italy. The fascist party is the rising star of the political landscape. Part of the power it will gain in the course of the forthcoming dictatorship will be due to the absolute control the Ministry of Propaganda will exert over radio and press.

Sales departments are the other actor that is making good use of the new media. They aim to shape the needs and tastes of the consumers into a more coherent model. And they are succeeding. People start to have the same habits, to speak the same language, to watch the same movies: more importantly, they start to want the same things.

The advertising business is getting ready to respond to this paradigmatic shift in consumers’ habits. In the past, admen were artists and artisans: they produced elegant posters, mostly art-nouveau and art-deco style, which were conceived to fascinate people, not to draw their attention. They didn’t need a compelling tag-line, nor a shocking image because they weren’t competing for the consumer’s eyes. Posters were few and scattered in a vast urban landscape so they could gently ask the passer-by to try this or that, without offering any compelling reason to do so. However, things have changed.

It’s easier to move products across the country in the twenties, more people fill the streets, and the rise of a homogeneous lifestyle makes people’s needs more uniform. Sales departments eventually understood that advertising could drive sales big time. So, walls and billboards are invaded by posters and neon signs, fighting to steal the smallest fragment of attention. Gentle advertising works no more.

Davide Campari knew that, right from the beginning. He was a businessman, an entrepreneur who inherited a small family business from his father Gaspare. The Camparis were initially based in Novara, near Milan, where Gaspare opened a bar. There he brewed and served Bitter and Cordial. The former is a ruby red aperitif made with herbs; the cordial was a stronger liquor, obtained from mountain berries macerated in cognac. After a few years, the Campari family landed in Milan, seizing a very central spot: they opened a couple of cafes in Galleria Vittorio Emanuele, Milan’s most famous arcade. And truth be told, Milan played a role in defining the way Campari developed his business. Valerio Varini is a professor in business history at Bicocca University: he describes the social niche Campari targeted:

“Davide Campari’s business was based in Milan, the first Italian market to experience the growth of consumer goods. Campari anticipated that if he had lowered the prices the company wouldn’t have got very far, so he targeted a specific social segment that asserted its dominance by purchasing elite consumer goods. He realized he could make a profit by selling a distinctive product to a niche whose members wished to be seen as the cream of society. In order to do so, he conceived something that conveyed more than its evident attributes: it wasn’t just a liquor, it was a symbol of luxury to be publicly consumed in the most fancy spot in town, that is the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele. Milan has played a pivotal role in launching the business because it was one of the few places in Italy where people adopted the same lifestyle you found in every European capital and, therefore, allowed Campari to experiment, check and recalibrate his moves. Milan was the perfect test bed for Campari: if he managed to sell his liquor as the elite drink there, it would have worked in any other city”.

However, this situation was a double-edged sword:

“The Galleria is the place where the Milanese elite used to spend its money. And by Milanese elite, I mean the artists, like Balla and Marinetti, who observed and narrated how society was changing. But there was also another kind of elite: entrepreneurs, industrialists, businessmen, those who were behind the push for economic development. Just by hanging out with his clientele, Campari got to know its tastes, its needs: let’s say, he kept his finger on the pulse of the situation. However, this precious spot could clip Campari’s wings in the long run, because by investing heavily in the cafes he would have limited his business to the local market. Campari wasn’t interested in competing with the other bars in the Galleria.”

He wanted something bigger.

The company was at a crossroads. There’s the quiet path: keep the business running, maybe open a few more bars, and became a town-size entrepreneur. And there’s the risky way: grow your business into a solid, international company and step up the production volume by building a factory. Davide Campari, now head of the family, chose the second option.

But great products and big modern industries were not enough to prevail in the new economy: Campari needed something more, it had to turn into a brand, to become a recurring word in everyday chitchat, to play a part in every family’s life.

Campari adopted a clever strategy. On one hand, the company stuck with a coherent image in order to become a recognizable brand in the long run. On the other, it changed the communication style as often as necessary, as exemplified by Varini’s analysis:

“Once more, Campari understood times were changing. He initially tried to forge a mental association in the customer’s minds between his product and Milan, which in the Italians’ eyes was a symbol of innovation. That’s why the label on the liquor said “Bitter Milano Campari”. After World War One, he felt that Milan was too small a bowl, so he associated his company with Italy: the liquor was then named “Bitter Italia Campari”. In the twenties, he changed plan again, since he noticed that nationalism, by closing the borders, fragmented the market. So he de-nationalized his product by remodeling the label – that now said just “Bitter Campari”. This way, every customer, no matter where he was from, was brought to associate product and brand instead of focusing on its national origins. Campari and bitter had to become synonyms.”

Campari had indeed been one of the first Italian firms to shape its advertising according to the ever-changing tastes of the customer. Sales knew which newspapers their customers read and studied the lifestyle Campari drinkers were accustomed to. Sales knew what people thought, what they wanted. But satisfying needs wasn’t enough: Campari planned to shape them.

A smiling woman offers you an aperitif, a romantic hero gulps down some liquor like a magic potion, sprites and satyrs peep from a black background – you’re looking at the first posters Davide Campari commissioned in the early years of the century. These works represented the introductions before a long-lasting dialogue between the firm and the consumer. The image they projected reflected the people’s taste: that’s what customers wanted to see, their language, their codes. As the consumers’ preferences changed so did the style. During the twenties and thirties, the company switched to a more aggressive vocabulary. Instead of diluting the brand in standardized, screamed ads – Davide Campari joined forces with various avant-garde artists who portrayed his company in the most alluring way. He gave them free reins, greenlighting concepts delivered by people having different backgrounds. Several artists concurred to create a more complex and modern image of Campari, where each personal style represented one tile of the broader mosaic. This kind of advertisement didn’t need any extra punch: inspired by avant-garde aesthetics, it was eye-catching as an ad can be without being vulgar.

So, ads conveyed art and art gave voice to ads. But Davide Campari wasn’t the only one who embraced this peculiar dynamic.

“The art of the future will be like powerful advertising. This bold lesson, this unwavering claim I learned by visiting museums, by studying the masterpieces from the past. The art from the centuries gone by aimed to advertise. The classical, archaic style of the past served to glorify the old days. Now we need a new, splendid art exalting our days, our glories. It has to be mechanical and quick – this new art shall promote movement, action, light and modern goods. The art of advertising is colorful, synthetic; it’s seductive and shines bravely on walls, on buildings, on trains, on the sidewalk, in store windows, everywhere”

This was an extract from the manifesto entitled “Futurism and advertising art”. Futurism was an Italian avant-garde movement that originated in the early twentieth century and lasted for almost eighty years, changing his skin, his rules, his principles, his goals. Futurism’s main focus is evident: in brief, the movement glorified modernity in its many shapes. Industry, technology, speed, youth, violence – everything new, all the stuff which came from the sparkling metropolis, all of that was good and exciting and worthy of a new narrative. Modern life needed to be exalted by modern art, a novel, creative force that pushed the boundaries of what was painting, music, literature, and so on. In a certain way, Futurism advertised a product, the future, using new languages, so it was just a matter of time until someone realized that the same thing could have worked the other way around. That advertising could be art. That’s what Fortunato Depero believed in.

Depero was the futurist who pushed more strenuously for advertising to be recognized as a form of art. For him, this wasn’t just a theoretical fight about the role of art in the modern world. It was personal. Depero had already been active in the advertising business for years when he decided to put his ideas into writing and composed “Futurism and advertising art”. In the manifesto, you can read the enthusiasm of a young, energetic man who knows the ins and outs of the business. But who was he? Was he an artist, a painter, a sculptor, an adman, or was he something else? Nicoletta Boschiero is the manager of the Casa d’arte futurista Depero, that is the Depero futurist house. Here’s her answer:

“Depero crafted pieces of textile marquetry, designed accessories and furniture. He wasn’t just a painter; during his life, he experimented with different arts and played different roles, which he changed accordingly. He has been an architect when he was charged with designing a commercial booth. He has done things that qualify him as designer, or at least as “proto-designer”, as performance artist, as poet. In the end, he was an artist who managed to explore new horizons by overcoming boundaries”

For starters, he worked in advertising by drawing sketches for posters and affiches. In the early twenties, he was based in Rovereto, a small town in Trentino. The town center is small and quiet. The paved streets didn’t change much since them, so strolling up and down the area is like walking through a time machine. Behind one of those peaceful corners hides the ponderous gate of Depero’s home. He spent his days working in a studio full of wondrous statues and paintings he made. Besides him stood Rosetta, his wife, sewing and modeling colorful tapestries. The door was always open because any stranger could be the next customer or a future patron. Depero transformed his house in the Casa d’Arte Futurista, House of Futurist art, that is a peculiar mix between an atelier, a workshop and a showcase for Depero’s works. Later, he moved his works into a bigger, more central location: the new address is 38, via dei Portici, where he started setting up his own gallery. Now you’ll find a museum there, the Depero futurist house.

Unfortunately, Rovereto wasn’t the kind of place where one can make a living out of advertising, not in the early twenties, at least. So, in the beginning, Depero traveled to Milan, which was, and still is, the industrial slash financial hub of the country. Boschiero explains how this worked:

“He was his own salesman: he packed everything up, said bye to Rovereto and left for Milan, where he stayed for a few days, trying to sell his art. He initially aimed to obtain commissions but after a while, he started looking for some kind of job in the advertising business; this search gradually became of the utmost importance to him. And while his hometown entrepreneurs couldn’t afford the services Depero offered, Milanese businessmen were right up his street”.

He used to spend days courting art directors to whom he showcased concepts and sketches. This allowed him to acquire his first clients while tasting the waters of the advertising sea.

There was a problem, though: he didn’t like the idea of moving to the big city because it would have meant to leave his wife back in Rovigo, the only person he could entrust with running the Casa Futurista. So he opted for taking short, solitary trips to Milan, back and forth, back and forth. Eventually, the strategy backfired, losing him several opportunities: he simply wasn’t there when he was needed. After he lost a juicy commission, Depero made a deal with his friend Fedele Azari. Azari had a long list of activities on his resumé: poet, painter, art collector, editor, airplane pilot, viveur – but for Depero, he was the guy who lived the city, who felt the vibes and intercepted potential contracts. All day, all night – he scoured sales offices for the best opportunities, while smelling the most promising firms in terms of business opportunities and aesthetic orientations. In some way, Azari was Depero’s guide and art-director: he stole important clients from advertising agencies and helped the young artist to make his works more appealing to a sales manager eye. The two worked in an assembly line: Azari found a lead and informed Depero who, in turn, crafted and sent him a concept. If it wasn’t quite right, Azari asked for a second or a third try, until they agreed the sketch was in line with the client’s expectation. And then Azari sold it.

Money was finally flowing into the duo’s pockets, while futurist art started to be the protagonist of a growing number of billboards in Milan. The artist was finally happy. Because these were the two things that Depero desired the most: to stabilize his income and to cheer up the world with joyful colors.

One of the most fecund ideas you may find amongst the often juvenile futuristic principles is expressed by the title of the manifesto: “Futuristic reconstruction of the universe”. The futurists stated their intention to decorate everyday life with bright, energetic colors. Let’s make the world anew, let’s have a laugh, let’s change whatever we don’t like – that’s what Futurism planned to achieve by implementing a new lifestyle inspired by vitalistic impulses … This all sounds promising and a bit troubling. It also seems very vague. What did this proclamation mean, in the end? How did this program plan to influence people’s ordinary existence?

Futurism aimed to change both the aesthetical and practical experience of everyday life. Instead of imprisoning art and beauty into dusty museum halls, the avant-garde promoted a pervasive diffusion of art. Your flat is grey and dull? Let’s revive it with colorful tapestries and some nice furniture. Perhaps in your daily commute, you’re expected to cross a depressing neighborhood, to walk down awful alleys or jump on dirty, sad trains? Then we shall cheer up the walls with bright affiches, we will cast our paintings on the clouds, we can make that train chromed and bold. Even the most insignificant detail of your routine – your toaster, your ashtray, your umbrella – could be saved and transfigured into something vital and new by reworking its nature according to Futurist guidelines. And do not worry, it will be an affordable revolution, for Futurism planned to launch mass production in order to cut the prices down and make art truly popular. Besides that, futurism claimed art was something wider, more complex than what people usually found in dusty museums. Here’s how Boschiero puts it:

“Applied arts played a role in this kind of Futurism. In the manifesto Futuristic reconstruction of the universe it is said that creating innovative items is the most important aspect of the reconstruction.”

To this end, Futurism pushed for applied arts, like furniture or automotive design, to be accepted as art tout court, instead of being considered some second-tier form of art. In the end, applied arts bring beauty to everyday life, and that’s what Futurism wanted and advertising could get.

Advertising was indeed the trojan horse inside which Futurist art hid to conquer the world. If you look at Depero’s works, both posters, paintings and tapestries, you will notice that they have several common features. Art historians talk about the so-called “Depero style”, which is a pictorial language focused on being joyful, energetic and full of colors. Depero carefully composed the image by juxtaposing shapes made of flat, striking colors. Those shapes form puppets and robots punctuating a uniform background. Depero’s knowledge of lettering techniques is also behind the eye-striking images that matched the new needs of the advertising business. Check out our site – italianculturepodcast.com – and take a closer look at some of his affiches. You’ll probably have the same feelings Davide Campari had when, in 1926, he laid his eyes on Depero’s work while looking for someone who could spice up his advertising strategy. Because it’s time that these two, Depero and Campari, meet in person. 1926 is the year industry and avant-garde collided.

Depero is frantic in his letters: did the meeting go well or was it an utter fiasco? He and Fedele Azari chased Davide Campari for months, sending sketches, concepts, trying to catch the uber-busy entrepreneur. When they met, Campari seemed interested but still hesitant: he was trying to decipher the young man and his art. Why is Depero so dramatic, now? Why so tense? Well, Campari is not just an ordinary business opportunity, he’s the “only chance, the sole solution”, as Depero writes to his wife. In the artist’s eyes, he represents the key to achieve the futuristic reconstruction of the universe. What a disgrace, what a misfortune, what an endless misfortune – that’s what Depero writes to Rosetta. Campari doesn’t make up his mind – the letter goes on – let’s hope he buys at least 4 sketches…He bought them. He definitely bought them, because in their second meeting he came to terms with Depero and forged one of the most significant partnerships the advertising world had ever seen.

First came the painting – Squisito al selz, Seltzer delight. It was displayed at the Venice biennale in 1926… This doesn’t sound quite right, does it? How is this possible? Depero, the one who talked about freeing art from museums, the futurist who planned to paint the streets in vermillion and cobalt – how did he end up hanging his painting in the Biennale? Well, you see – this is not a regular painting, nor an affiche. This is a quote/unquote “advertising painting”. Take a look at it, you’ll find it on our site: italianculturepodcast.com. You’ll see a bar and within the bar a couple of men, sitting at a couple of tables while looking at a couple of soda siphons spraying seltzer in a couple of conic glasses. In the background, you’ll read the words -Bitter Campari-, flashing like a neon sign hanging from the wall. According to Depero, this is art in its purest form. Cast aside all the theoretical speculations, stop claiming aesthetics is a frigid reign of ideas. Art is not pure. Art is functional, it serves a purpose, it has always been like that. Once it celebrated the heroes, the generals, who were portrayed as naked, triumphant gods. Nowadays, modern art glorifies modern heroes. And who are those champions, you may wonder? Easy: industrialists, businessmen and entrepreneurs, those who keep our needs satisfied, those who make the modern world spin around its axis – those are the men of the hour. And that’s what Squisito al selz is, nothing more, nothing less than the highest praise to the company producing seltzer. Campari loved it.

But this, this is just the beginning. The advertising material Depero produced in the next four years is simply astonishing, not only because of its quantity but mostly because of what it meant to the marketing world. Boschiero:

“He was able to modernize marketing communications, as it has previously been performed and codified by giants such as Dudovich. For instance, Depero changed the rules of newspaper advertising by creating funny cartoon-like ads”

One can only imagine how people of the time reacted to the small affiche portraying a robot, or more precisely, a mechanical gentleman who’s strolling in thick rain while he drinks from the handle of an upside-down umbrella. The tag-line is “if rain were bitter Campari”. Or what about the puzzled guy whose conic head ends with a glass of Campari? Here the pun is even simpler: drink too much Campari and it will go to your head. But still, drink it. This all may seem naif, even silly to us – children of the viral, digital marketing era – but this form of communication was something exceptional in the early twentieth century, when people were accustomed to more plain forms of advertising.

Besides drawing sketches, Depero implemented a 360 degree campaign that involved mosaics, pieces of furniture (like lamps and trays), an advertising booth made of letters spelling the word Campari – and so on. He also assembled one small billboard, mounted on a tripod, that was meant to be positioned on the bar to advertise Campari drinks. To be more precise, he designed the whole bar, which was planned to open in New York. And since cinema was the main form of mass entertainment back then – he crafted a set of removable backdrops, that should have been displayed during the intermission. You know – he went one step further: why being just an off-screen diversion? Why Campari couldn’t be the protagonist, right there, right on the screen? We don’t know much about this project, but we do know that Depero began work on a script for a Campari film that never saw the light, as many concepts of his.

One can clearly see the efforts Depero put into developing an all-round campaign for Campari. However, as already anticipated, this relation wasn’t just a business contract. It had a vaster meaning to Depero. The commissions Depero received from Campari allowed him to perform art in the way he thought it was meant to be. And that was instrumental in his futurist plan of rebuilding the very foundations of the modern world. It’s not a surprise, then, that Depero’s most famous art manifesto – the so-called bolted book –– opens with a dedication to Davide Campari, described as “a brave and chosen friend of artists, who – for his generous collaboration – merits my humble thanks”. Partly flattery, partly true acknowledgment – this dedication tells what Campari and Depero were to each other, before and beyond being patron and artist. They were “collaborators”, which, in brief, means they were on the same mission of changing the world while getting rich.

Dreams of a country boy who embraced the future, they were not: honking cars, busy streets, looming skyscrapers and rumbling trains. Depero was one of the few Italian futurists who actually lived the modern life. And tasted its bittersweet flavor: from 1928 to 1930 he lived in New York and conducted business there, proposing his concepts to sales and art directors as he did in Milan. And when he finally reached the peak of modernity, the heart of what is new, quick and bold – that’s when his trust in the future betrayed him.

The filth, and the smoke, and the clamor. The loneliness, the alienation, the misery. Real life in New York wasn’t kind to Depero. When he landed there, he didn’t speak a word of English and had very few contacts. A friend gave him the keys to his office in Brooklyn: Depero slept there but had to leave every morning before work hours, which he spent walking the streets. During these long hours, he discovered how city life isn’t necessarily a blessing bestowed on us by modern times, especially if the suburbs you roam don’t reflect the lights of Broadway. Modernity showed Depero its hidden face, eroded the trust in the future he once naively shared with his Italian comrades. That’s how Depero fared back then, according to Boschiero:

“Despite his name – Fortunato, which means lucky – Depero landed in New York at a very bad time, on the eve of the Wall Street crash. If it wasn’t for his advertising art, if he had been -let’s say- a regular artist, he wouldn’t have made it. His tapestries, his creations were perceived as artisanal, even homespun, by Americans – people who were accustomed to certain standards, typical of an industrialized country. His love for the advertising business was the ace up his sleeves”.

After a while, he was joined by Rosetta, who helped him to open and run a futuristic house in New York. Art critics started to visit the atelier and seemed to appreciate Depero’s work, its novelty, its groundbreaking style. Their support was worth a few personal exhibitions in prominent spots, like the Advertising Club or the Guarino Gallery. Despite the moderate success of his art amongst the artistic community, Depero wasn’t receiving any commission yet. His letters to Fedele Azari tells us a lot about what was going on behind the curtains. Apparently, he found New York life boring. The art market was even worse. According to Depero, art exhibitions were the play-grounds for a flock of parvenu who used to show up, have a chat and pose in their designer labels. Needless to say, they didn’t understand a thing about art. And they bought even less. To cut a deal you needed an executive, but they only purchased ancient art and such. Their taste in arts was plain, soporific: a little bit of modernism here and there, but God forbid buying something avant-garde! It seemed to Depero that, unlike Europe, the United States had an elite-less society: no-one felt the urgency to experience something new, to set a trend other people would follow. Everyone was just too busy making money, they had no time to deal with art.

Too late for Philip Hone, too early for Peggy Guggenheim, apparently.

In the end, Depero tried a rather curious publicity stunt to save the day and prolong his stay in New York. Prospects and patrons weren’t in for his art? He only had to change the bait: instead of luring them with the promise of an art soirée focused on avant-garde – he used ravioli, Rosina’s ravioli. After all, everyone loves Italian food, right? So, he invited twenty people and had them sit around a table, just in the middle of the atelier. It was lunch-time and people were getting hungry. The artist served them plenty of ravioli, together with a load of Italian dishes, each one carefully cooked by his wife. While they were eating, he showed them a few of his works, pointing at the paintings hanged on the walls all around them. Apparently, the pleasure of eating home-cooked food made the audience malleable because, at the end of the meal, Depero acquired contacts, sold some pieces, and received a few commissions too. For instance, he was charged with drawing a couple of covers for Vogue Magazine. But again, he had a rough time convincing people to accept Futurism: a few notes from the Vogue’s art director describe Depero’s works as quote/unquote “a bit wild, a little bit too much” or “a little bit too heavy and lacking in fashion feeling”.

So, all in all, did Depero manage to earn enough money to prolong his stay in the States? No, he didn’t.

That’s why in 1931 he came back to Italy. It was time to finalize his next big thing.

One would say that while Depero was in New York, he was so busy making a name for himself in the advertising business that he forgot about Campari. That was not the case.

During his last American year, he worked on a special Campari project, the “Numero unico futurista Campari”, that is the “Campari special futurist issue”. It’s a book, conceived as Christmas present sent by Campari to prestigious partners and such. Inside, you’ll find a collection of Campari advertising material. Every page is covered in posters and affiches. Readers were supposed to look at these pictures while listening to a custom tune, whose score has been printed on one of the pages.

If you carefully read the Numero Unico, you’ll notice that it has a certain way to convey ideas. Depero was running some tests on something we can call the “choral approach” to communication, according to which images, words and music harmonically cooperates to convey a message. What does this mean? Let’s take the short poems you find in the book. The words are embedded within drawings, so that both elements – poems and drawings – engage in some sort of conversation. Instead of repeating the same concept in words and pictures, Depero used two channels, writing and drawing, to convey two messages that, while interacting with each other, blend into one. For instance, look at the poster portraying Campari’s liquors as traffic lights – you can see it on our site: italianculturepodcast.com. This poster suggests that drinking Campari somehow regulates the dynamics of modern life. The poem, printed on the next page, complements this message by telling the story of a sad man who reaches happiness through a three steps process. These three phases are symbolized by the three lights of the Campari traffic signal that drives the sad man towards a glass of cordial.

This peculiar code of communication mixes with a rather modern narrative strategy. Depero noticed that successful marketing operations didn’t just sell the product. They rather created a world in which the product had meaning and then lured the consumer in it. So, instead of proposing to exchange a few coins for a delicious drink because, you know, it tastes fine, Depero invited the customer in a realm of dazzling, solid light. He tapped into the futurist symbolism to portray Campari as the core of the modern electric world. In these affiches, the bottle of bitter is represented as a beacon guiding people towards the future, or as the pulsing heart that animates a skyscraper. Campari is what the future looks like, and everyone can taste it, just by sipping a liquor. Trust, joy, smiles and youth – one carefree embrace in which one may thrive – that’s what drinking Campari means, that’s the paradise of steel and glass whose doors Depero opened for the years to come. Until they closed.

The Numero Unico is considered to be the last and most significant product of the Depero-Campari collaboration. From 1931 onwards, Depero gradually drifted apart from Campari and advertising in general. He still entered a few competitions to develop advertising campaigns but he lost the enthusiasm he once felt for the business. The advertising world also took another turn, embracing new trends that shared less and less with the Depero style. However, the seeds he sowed during the years he spent working in the field were silently germinating, bounded to give fruit in due time. That’s why, in order to understand what happened next, we’ll need to go back in time a little bit.

It’s summer, the year is 1926. The hottest season can be infamously hot in Italy. So, there you have it: flocks of people flood the highways, rushing to the nearest beach.

One of the primary goals of both professional and amateur sunbathers is to keep the body hydrated or, in the late afternoon, to keep the party going. Thus, Campari commissioned Depero a series of sketches for a vending machine to be placed by the seashore, so that thirsty sunbathers could get a cool sip of Campari drinks without vacating their fighting positions for too long. The artist reworked a few old drawings and sketched the vending machine you’ll find in our photo gallery, at italianculturepodcast.com. On the top of the structure, there’s one of Depero’s robots. The puppet appears to be sucking Campari from a straw. The straw ends in a conic bottle, a recurring theme in Depero’s works. That oddly-shaped bottle is probably the most ubiquitous and long-lasting legacy Depero left to the modern world.

Fast forward to Sunday tenth of July 1932 – another hot Italian summer. This time, we’re in Milan. It’s noon, the sun is at his peak and nobody dares to cross the streets, whose asphalt is silently melting. A solitary man approaches the newspaper stand and buys the newspaper. He folds the paper and uses it to shield his head against the oppressive sun rays. He hasn’t noticed it yet, but on the cover, there’s a full-page ad paid by Campari. Apparently, the liquor company hasn’t forgotten those who linger in the city while the summer advances. A new product has been destined to alleviate their thirst: it’s called the “Campari Soda” and it tastes like the cocktail you were used to drink at a bar. But thanks to this new product, you won’t need to leave your sofa to have a sip of it – not anymore. Besides that, there’s no need to mix and stir and shake, because the preparation had already been completed before the bottle left the factory. It also responds to a different kind of demand. Valerio Varini:

“We’re in the late twenties and Italy, like other countries, is going through a harsh economic crisis. As a consequence, consumption is rapidly decreasing. Campari and his company are at a crossroads. Either he drops the prices, or devises a strategy that keeps the profit stable while adjusting sales and goods to the new purchasing power. That’s how the Campari soda was born: it’s a single-dose bottle and, therefore, is way cheaper than the normal format. This was clearly meant to encourage consumers, even those who were in dire straits, to buy the product.”

Quick, hygienic, affordable and young – the Campari Soda was meant to be the modern way to enjoy a glass of liquor before dinner. This allowed Campari to offer a homogeneous, controllable drinking experience while attaining industrial standards in quality control and distribution. So, from a production standpoint, the Campari Soda can be considered a step toward a larger scale model of consuming pre-mixed drinks. If we look at the changes it introduced into material culture, we notice that this new way of consuming cocktails somehow gave a modern twist to the old aperitif tradition, changing the way mixed drinks were consumed. However small, this change was part of the futurist life, as it was foreseen by Depero: an energetic-hygienic red drink pouring out of a conic bottle belonged more to a spaceship than to post World War I Europe. Speaking of which, what about the bottle? Is it up to its tasks?

Shaped by the blazing fires of the Bordoni glass-factory, this tiny bottle contains enough liquor for one drink. It’s made of transparent glass and has no label on it, so that the red liquid shines through the vessel. How can you tell it’s a Campari Soda, then? Instead of wrapping the bottle in a label, the company opted to emboss its name – Campari – on the surface of the bottle so that nothing stands between the eye and the product. This whole setup is simply revolutionary if you think it through. You are probably familiar with a caption accompanying many ads: it’s printed in small letters, and admen love to hide it somewhere in the ad. However, it claims something important, specifically that “product images are for illustrative purposes only and may differ from the actual product”. This caption points out how much advertising mystifies reality. The Campari Soda bottle, on the contrary, erases the distance between advertising and reality by making image and product converge: there’s no need for a label, no photoshopped poster alters the appearance of the liquor – here the product speaks for itself. Thanks to the label-less, transparent container, the most iconic feature is always under the spotlight, in the foreground. When you look at Campari soda you don’t see a bottle full of red liquor, you see a cone of red: the whole product is that redness. When you pop a bottle and sip its content, you’re not drinking Campari and Soda Water, you’re drinking liquid red light.

Dynamic, hygienic, industrial, modern, full of light – as the tagline on the newspaper ad claimed – “Campari Soda is brewed in one majestic machinery that has been made for it”. What is more futuristic than that? The Campari bottle is where industry and futurist art actually come together: someone calls it industrial design. One thing is certain: the bottle is pretty and functional, and is now part of everyday life. It hasn’t reconstructed the world from the ground up, but it’s nice to have it there, it’s a little fine thing.

In the end, who takes the credit for this small wonder?

No-one has ever found a signed sketch that formally links the Campari Soda bottle to Depero. Boschiero confirms scholars scoured the archives and found nothing substantial. Considering his effervescent personality and what his art was meant to express, it’s highly unlikely that Depero actually drew the bottle destined to mass-production:

“Among other things, Depero never talked about the bottle. If he really was the man behind the sketch, he would have certainly said something – in the end, his art has always been some sort of self-narration. Take the tapestries he made. Each one of them is like a short story, -let’s say- a recap of Depero’s life. One narrates Depero’s stay in Capri, the other describes his hometown or the carnival of Viareggio. He even made some references to his past works, such as the balli plastici or the devil’s cabaret. In brief, every piece of art was a chance Depero took to self-promote so that whoever has looked at his works has been able to recognize his hand, to reconstruct his life at a glance. That’s the Depero’s style. So, that said, it would be odd if Depero was indeed the one who created the Campari soda bottle and never told anything about it”

On the other hand, Depero has been universally acknowledged as the man behind the design. Why’s that? Well, you won’t need extensive studies to discover the reasons why he most probably inspired the actual, unknown designer. If you look carefully enough, you’ll notice that the conical bottle features in plenty of Depero’s drawings, from Squisito al Selz to the late New York sketches. Even the puppet on the vending machine is drinking from the same flask. All the traits that made the bottle an icon are already there, except for one – the transparency. No one knows who came up with the idea of removing the label and using transparent glass. It was probably someone from the company, perhaps Davide Campari himself. But, in the end, who really cares about who has more merit? Depero? Campari? Neither and both. This was a collaboration, after all.

0 Comments